"The Animals Are Talking. What Does It Mean?" in the New York Times magazine (20 Sep 2023) by Sonia Shah features lovely illustrations by Denise Nestor. The article's theme is language — and whether (or to what extent) humans differ from (other) animals in communicating and thinking via symbolic abstraction.

Shah's summary of the subject:

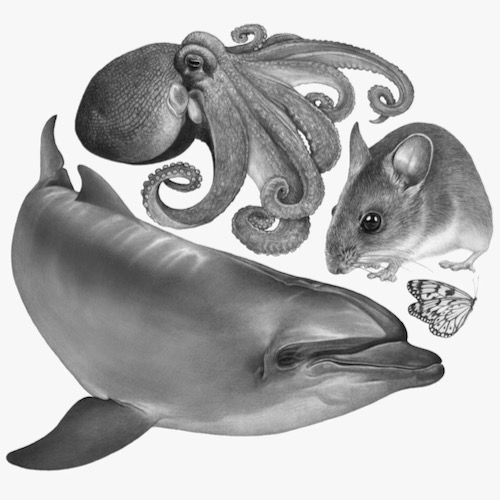

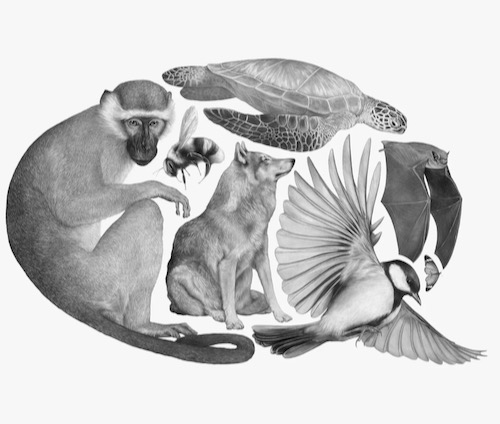

But the rudimentary skills of mice suggested that the language-critical capacity might exist on a continuum, much like a submerged land bridge might indicate that two now-isolated continents were once connected. In recent years, an array of findings have also revealed an expansive nonhuman soundscape, including: turtles that produce and respond to sounds to coordinate the timing of their birth from inside their eggs; coral larvae that can hear the sounds of healthy reefs; and plants that can detect the sound of running water and the munching of insect predators. Researchers have found intention and meaning in this cacophony, such as the purposeful use of different sounds to convey information. They’ve theorized that one of the most confounding aspects of language, its rules-based internal structure, emerged from social drives common across a range of species. With each discovery, the cognitive and moral divide between humanity and the rest of the animal world has eroded. For centuries, the linguistic utterances of Homo sapiens have been positioned as unique in nature, justifying our dominion over other species and shrouding the evolution of language in mystery. Now, experts in linguistics, biology and cognitive science suspect that components of language might be shared across species, illuminating the inner lives of animals in ways that could help stitch language into their evolutionary history — and our own.

Other creatures share key genes that enable human speech (e.g., FoxP2). They have common anatomical structures to generate and modulate air vibrations. They have similar neural circuits "to learn and produce novel sounds".

Squabbles continued over which components of language were shared with other species and which, if any, were exclusive to humans. Those included, among others, language’s intentionality, its system of combining signals, its ability to refer to external concepts and things separated by time and space and its power to generate an infinite number of expressions from a finite number of signals. But reflexive belief in language as an evolutionary anomaly started to dissolve. ...

Experiments with symbol-codes "... suggest that language’s mystical power — its ability to turn the noise of random signals into intelligible formulations — may have emerged from a humble trade-off: between simplicity, for ease of learning, and ... 'expressiveness,' for unambiguous communication."

And there's room for strange syntax:

... the communication systems of other species might, in fact, be “truly exotic to us,” ... A species that can recognize objects by echolocation, as cetaceans and bats can, might communicate using acoustic pictographs, for example, which might sound to us like meaningless chirps or clicks. To disambiguate the meaning of animal signals, such as a string of dolphin clicks or whalesong, scientists needed some inkling of where meaning-encoding units began and ended ... If scientists analyze animal calls using the wrong segmentation, meaningful expressions turn into meaningless drivel: “ad ogra naway” instead of “a dog ran away.”

Seems like we're all One on this funny planet ...

(cf Key to the Treasure (2004-04-23), Other Minds (2023-10-12), ...) - ^z - 2024-01-08